In a World of Limits, Choose Freedom

More than a function of throttle position, Wide Open is an expression of our core philosophy. We recognize no boundaries and accept no compromise. Where others perceive a barrier, we see an opportunity. We create premium marine power to take you faster and farther. We give you control to shatter expectations. The world offers limits. Mercury Racing offers freedom.

The Art of Speed

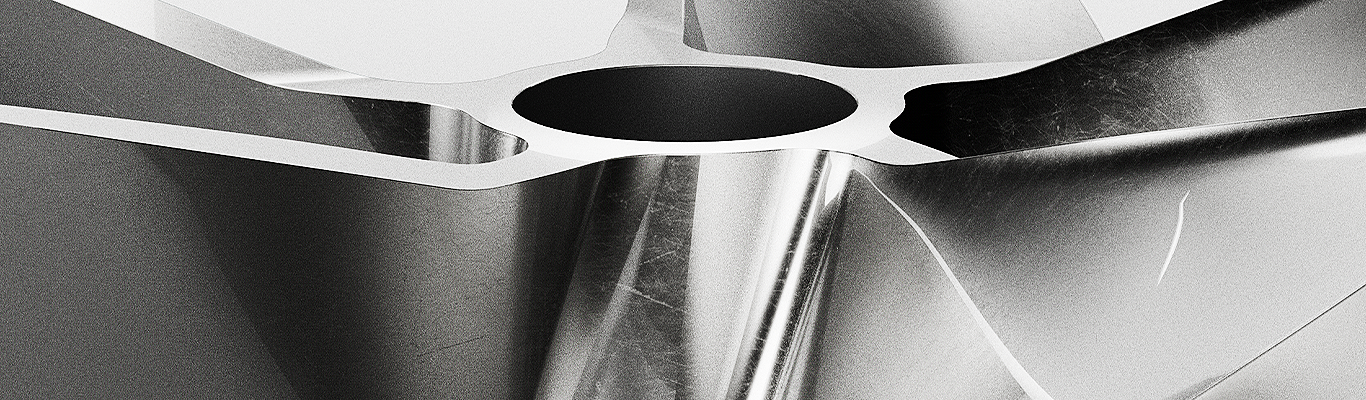

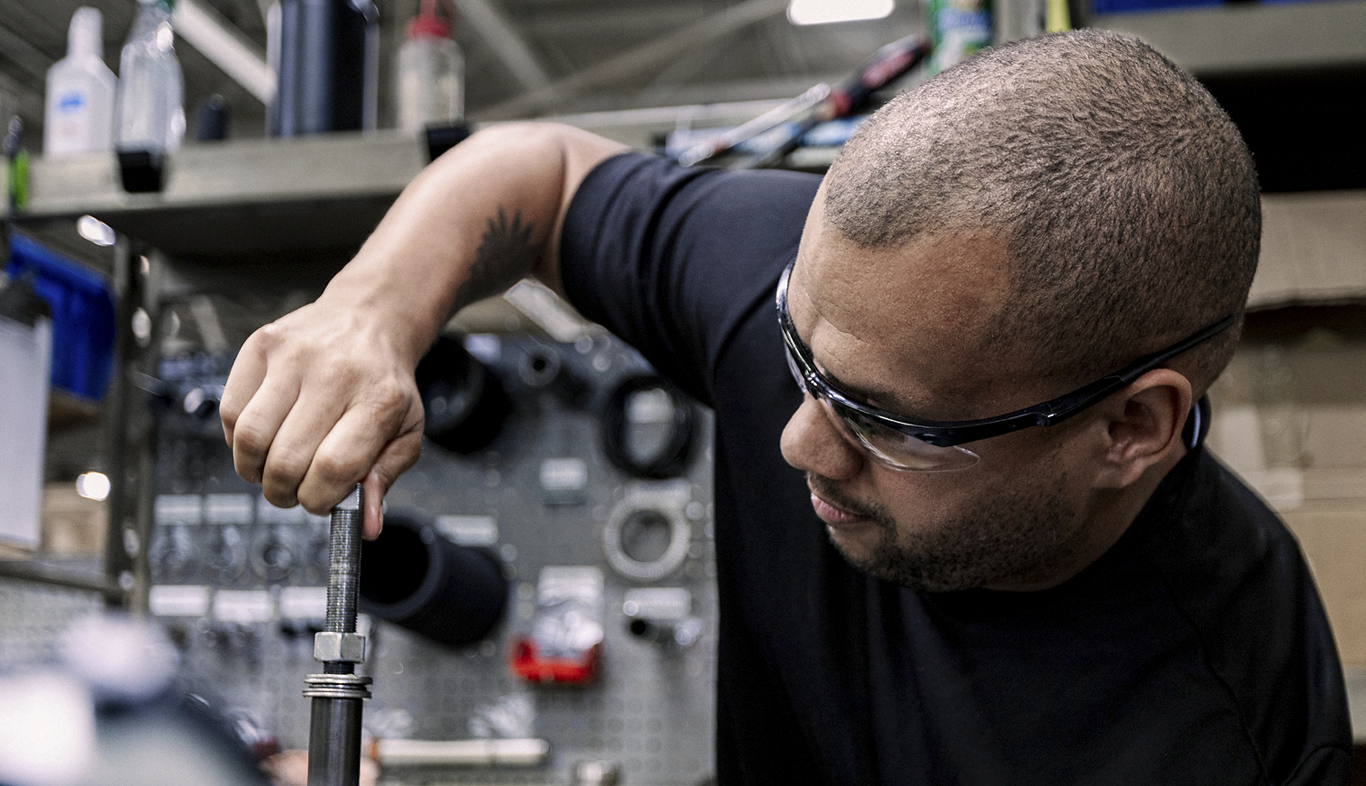

Mercury Racing Propellers offer the ultimate in performance and durability. Our propeller artisans handcraft each prop into precision tuned works of art.

DiscoverWe Never Settle

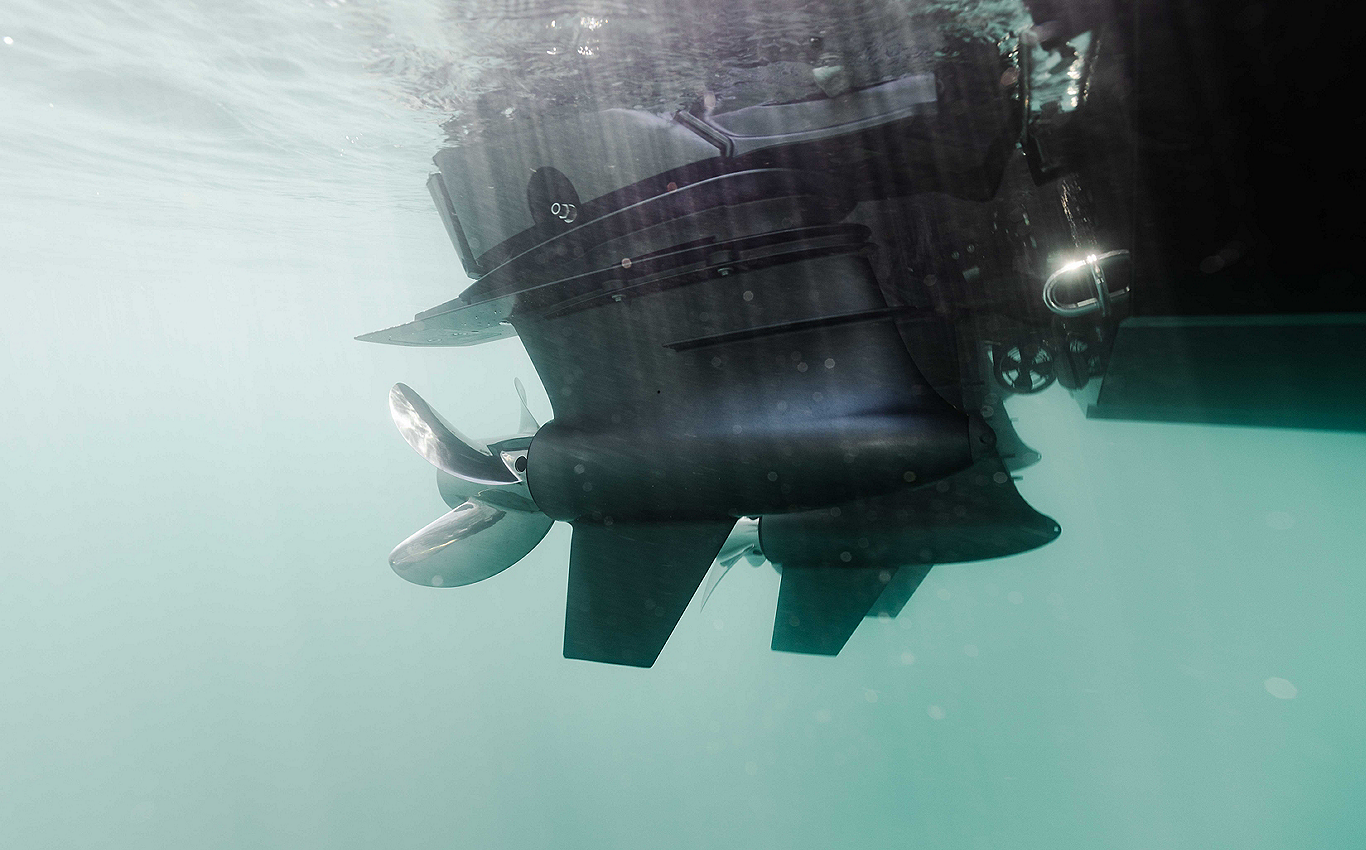

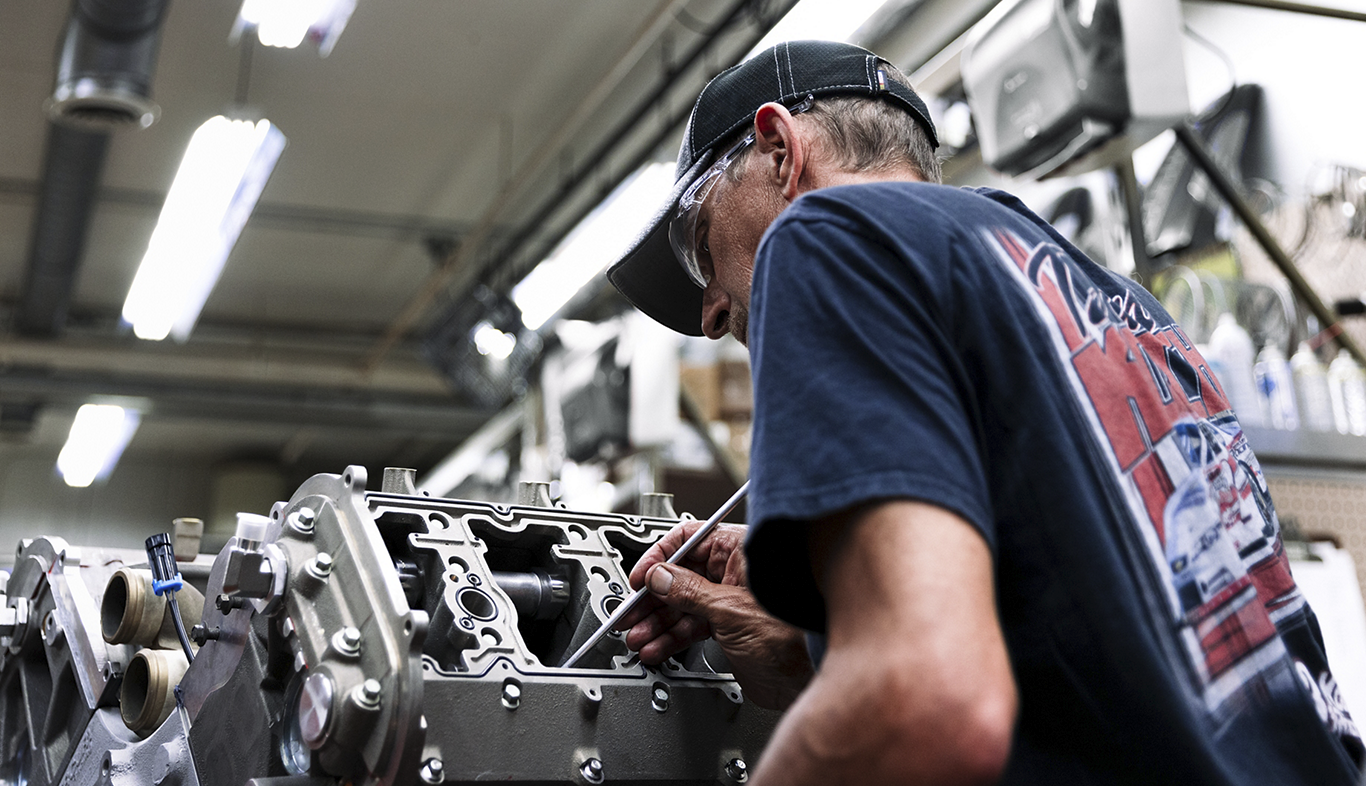

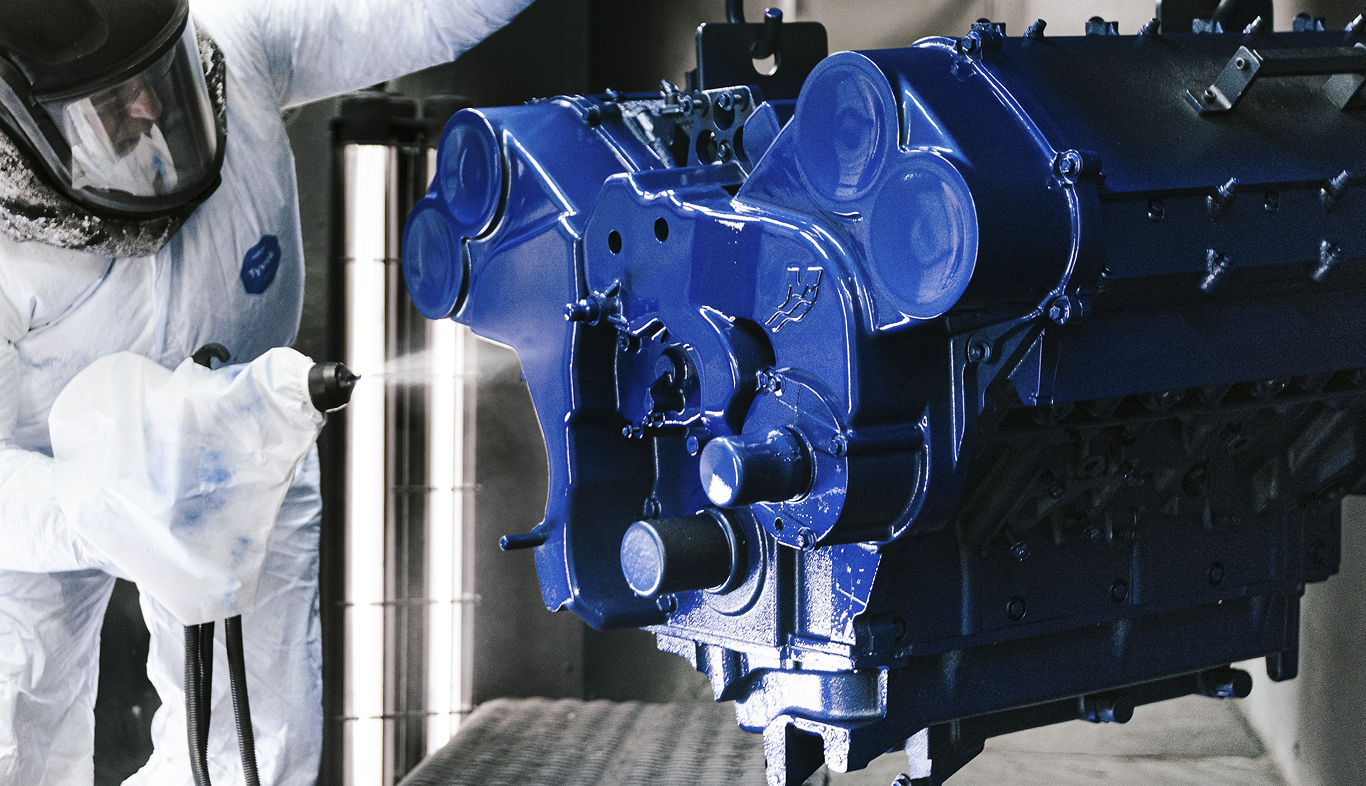

We turn ideas into metal, concepts in horsepower, and horsepower into speed. We leverage technology and creativity, science and craft. We invest in unbeatable experience, facilities and resources. We are always out to win. We are racers. The pursuit of speed is our passion. The water is our venue. The goal is to put our customers out front. And keep them there.

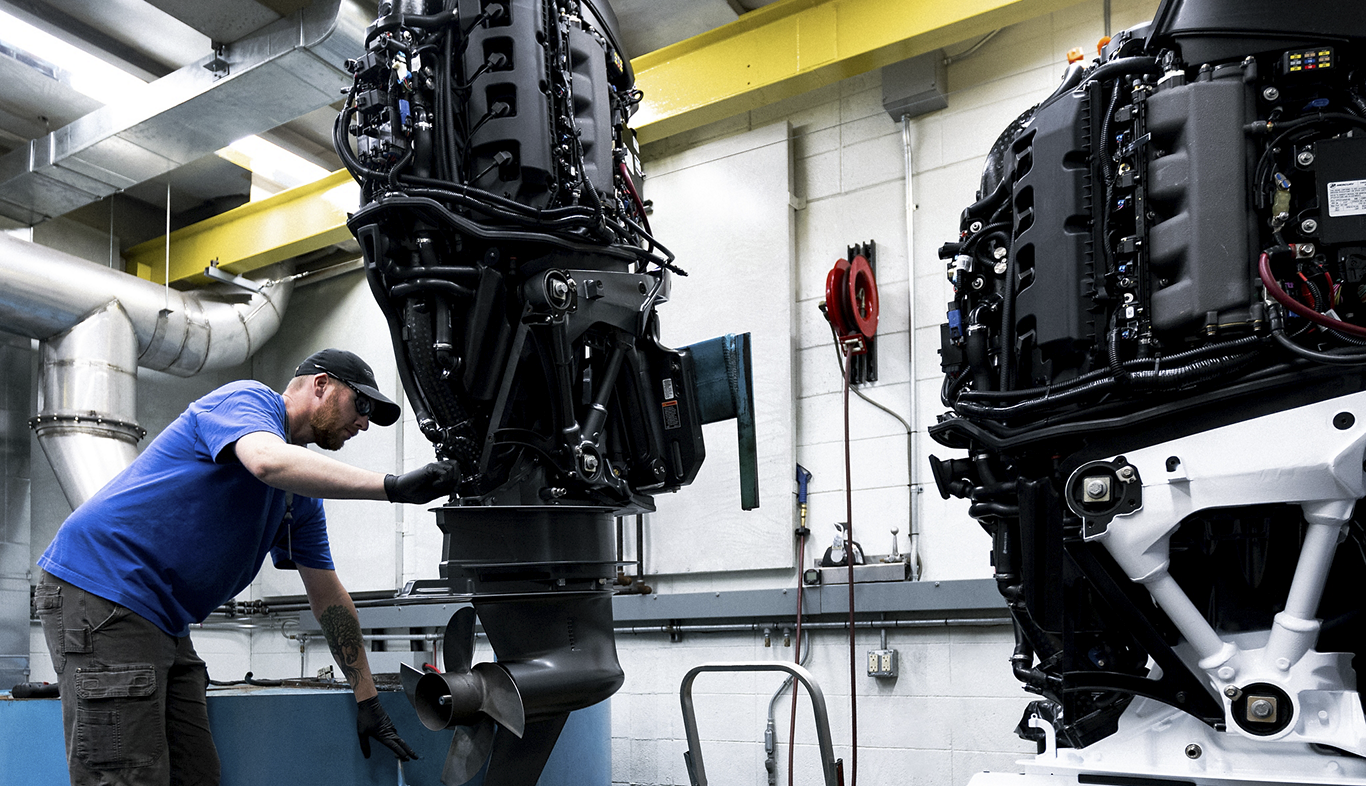

Apex Series

Passion. It's what defines the Mercury Racing Apex Series, pure competition outboards designed to perform at the pinnacle of closed-course racing - the quickest, fastest, smartest four-stroke outboards to ever boil the water.

Discover